“For me, it's not just a job, it's a mission”

2025

Jul

18

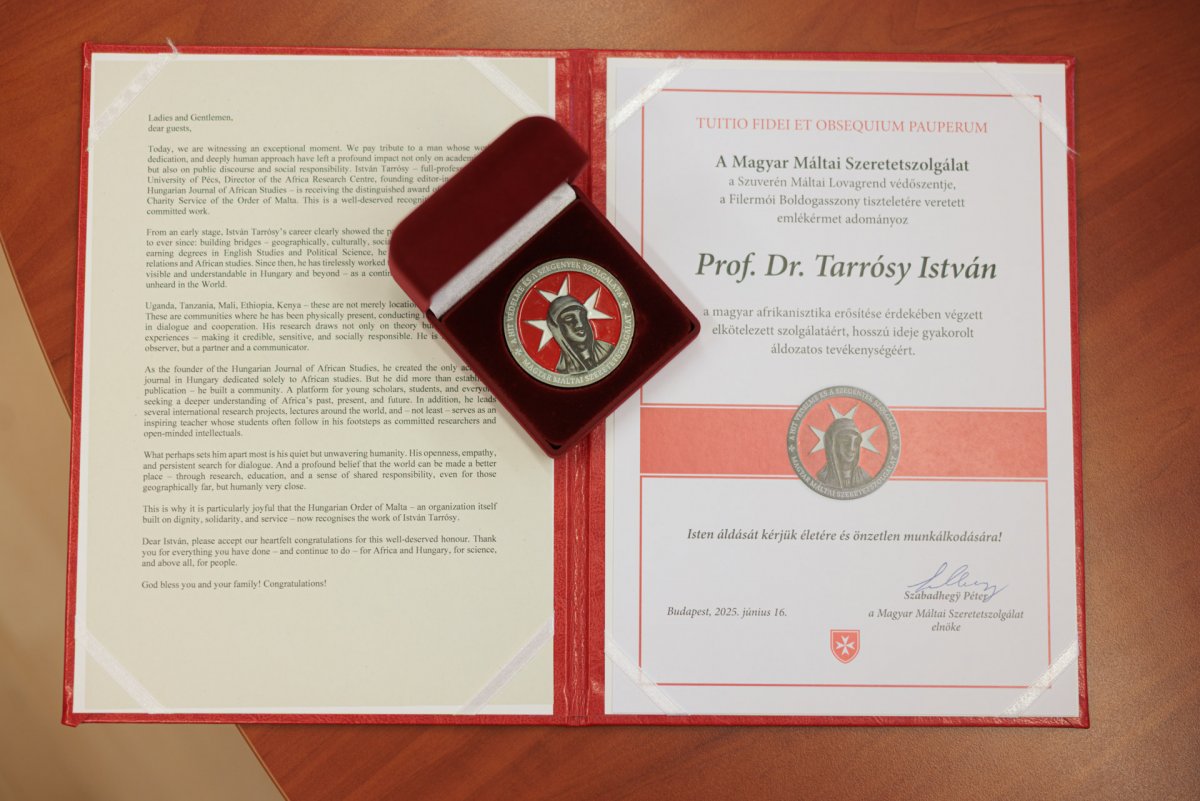

Africa. A continent that captivates many. It was no different with Dr. István Tarrósy, Director of the International Centre of the University of Pécs, Professor of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, founder of the PTE Africa Research Centre, who recently received the prestigious award of the Medal of Merit of the Blessed Virgin of Filermo from the Hungarian Charity Service of the Order of Malta in recognition of his decades of work in the field of research on Africa in Hungary and Central and Eastern Europe.

Heartfelt congratulations on the recognition! What does this award mean to you?

Of all the awards I have received so far, this one perhaps resonates with me the most, as it reflects nearly three decades of work focusing on topics related to developing regions, whether from a scientific or public engagement perspective. This award is particularly close to my heart because it is about Africa and the activities and causes that matter most to me, and evidently, to others as well.

Although I have not worked directly with the poor, my aim has always been to draw attention to issues that contribute to reducing social inequalities. This approach has also been a guiding principle in building professional relationships. I did not expect such recognition, which makes it all the more humbling and an extraordinary honor to have my work acknowledged in this way.

What led you to focus your work on Africa?

As a young adult, I spent some time in England, attending the University of Leicester in 1998-99. I found myself in an inspiring environment: I was surrounded by excellent lecturers, exciting courses, renowned researchers and subjects that had a lasting impact on me. In this multicultural city, the student body was also diverse, with several young Africans as my classmates, which broadened my horizons and made me even more sensitive to global contexts, international processes and dynamics.

Back in the day, there was a university newspaper called Pécsi Campus, considered the predecessor of what is now UnivPécs Magazine. In my opinion, it was the best among all such university publications in the country. It was under the editorship of my friend, Laci Bellai, in the late 1990s we made an informal agreement: if I made it to the UK to study, I would serve as a kind of correspondent from abroad. This was in 1998, and even then, I was writing articles for the university paper on Kenya and East Africa. It's a deeply gratifying feeling to look back and realize how early I began researching these regions, and how naturally they found their way into my field of interest.

In 2000, my fate was sealed when I first travelled to Tanzania in sub-Saharan Africa, followed later, on the return journey, by a visit to Egypt. It was an immersive and complex encounter with Africa. That was when I caught what Zsigmond Széchenyi once called the 'Africa virus' (or Africa bug), a feeling that deeply affects those who experience the continent firsthand. For me, it sparked a lifelong attachment and an enduring curiosity. I was left with what I now call an African heart.

You liked it so much that you helped to set up the Africa Research Centre at the University of Pécs!

Yes, we founded it together with the late professor Sándor Csizmadia at the then Faculty of Humanities, under the deanship of professor Ferenc Fischer, who strongly supported launching such a university center.

Last December, we celebrated the 15th anniversary of the center with an international PhD student conference.

But even before that, we were engaged in Africa-related research activities that practically predestined us to establish the country’s first interdisciplinary research center within a higher education institution. The initiative has been operating steadily ever since. We actively organize scientific, intercultural, and educational events and coordinate the work.

It quickly outgrew its initial boundaries and has now developed into a genuine university-wide, interdisciplinary unit that involves colleagues from various faculties at the University of Pécs and other universities across Hungary. We've created a knowledge network and hub where experts from diverse fields – geography, international law, political science, economics, anthropology, linguistics, and even music – reflect and collaborate on Africa.

Currently, for example, a Kenyan PhD student is conducting research in the Institute of English Studies. He’s a certified Swahili teacher. This spring, we involved him, on a pilot basis, in the “African Studies” course I teach, reintroducing Swahili language into university education. I’m hopeful that from next year, it will become part of the official curriculum.

In fact, we are launching a specialization in “African Studies” within the International Studies MA program, where Swahili will be offered as a dedicated language course.

This is important because Swahili is spoken by around 200 million people and serves as the lingua franca of the entire East African macro-region. Anyone looking to work in or with Africa – especially in that area – would benefit greatly from acquiring it.

You also do fieldwork. Are there any specific projects, results, or collaborations you are particularly proud of?

Yes, my colleague Zoltán Vörös and I have been working on a research project since 2018. We are conducting fieldwork in Ethiopia, studying two major Chinese-financed and –built infrastructure projects: the Addis-Ababa light rail/tram system and the Addis–Djibouti railway, which spans about 760 kilometers and connects Ethiopia’s capital to the port of Djibouti. This latter project is especially critical, as Ethiopia – being landlocked – is at a significant geopolitical and commercial disadvantage. The loss of its sea access was a consequence of the war with Eritrea, making it vital for the country to reconnect to global trade routes.

We return every January and systematically document the development of these projects, the emerging challenges in maintenance, financing, and operations.

This kind of long-term, continuous observation is a rare gem in international field research. We can already show, for example, that the repayment of Chinese loans imposes a considerable burden on Ethiopia’s budget. We also examine the project's technological and institutional viability – are there energy problems, maintenance issues, political obstacles? Our research contributes not only to understanding China-Africa relations but also to grasping the broader transformation of the region.

The studies and articles that emerged from this work have received international attention beyond our expectations:

our materials have been used in U.S. government background reports, cited by Chinese and African experts, and referenced in the work of European researchers. Citation data clearly show these publications are not only unique but also fill a critical gap.

Another essential pillar is institutionalization: the center, the language courses, the interdisciplinary connections. Thanks to all this, the work didn’t remain just a personal mission, but became institutionally embedded. My doctoral dissertation, for instance, was written on Tanzania. I was interested in how the current Tanzanian state structure and political system developed following independence, specifically after the establishment of the United Republic of Tanzania in 1964. I examined governance, decentralization, international integration, and regional dynamics.

Alongside the political science focus, I became deeply engaged with a very serious social issue: the persecution and security challenges of individuals with albinism (PWA) in Tanzania. The global media began to report on this in the late 2000s, when it came to light that PWA individuals were being literally hunted due to certain occult beliefs.

I worked on this project for eight years, addressing security policy aspects, social embeddedness, and conducting fieldwork with local communities. The resulting article was eventually published in a leading African Studies journal, although it was the product of years of work. The publication process was often challenging, but today the article has become an important reference in the field.

The award's name includes the "Blessed Virgin Mary" ("Boldogasszony" in Hungarian), which suggests a value system. How do you connect your scientific work with humanity and service?

I deeply believe that all true knowledge should serve humanity and humanness. I’ve always taken the idea of service seriously: if I commit to something, I do so with full dedication. This is how I approach my university work as well – I’ve served the University of Pécs and its predecessors for over thirty years. For me, this isn’t just a job – it’s a kind of mission. Teaching is a form of service, a devoted service to knowledge and its transmission.

You’ve been researching Africa for nearly three decades. Do you see a shift in how Hungary perceives the continent? What role does the Research Center play in this?

We play a key role in this process, although it’s not an easy task. One of the first major steps of this mission from Pécs was launching the Hungarian Journal of African Studies in 2007. It’s been continuously published ever since, in open-access format, and now two of the three annual issues are in English. We’re seeing a growing number of international authors – especially African researchers – who would otherwise struggle to get published due to the exclusivity of the Anglo-Saxon academic publishing space.

This journal has always been part of a clear mission: to ensure that Hungary contributes to expanding, maintaining, and strengthening the corpus of accessible knowledge on Africa. The goal is to better understand this diverse continent.

That’s especially crucial today, as the world order is transforming and Africa is once again in the global spotlight. Everyone knows the history of colonization, but there’s less discussion about how some actors still approach Africa with similar mindsets today. But African countries now firmly reject this: they say, “If you cannot treat us as partners, we won’t work with you.” Instead, they turn to other global or regional actors, such as Turkey, especially those from the Global South who have gone through similar challenges.

In line with this, our Research Center is active on multiple fronts: not only do we organize scientific conferences, but also open university lectures targeted at the local community. We are active nationwide too. For example, in collaboration with the Hungarian Charity Service of the Order of Malta, we previously organized a national lecture series, and we plan more. Our goal is to bring Africa closer to people in all its diversity, whether through an engaging concert, an exhibition, or a thought-provoking lecture.

You made a powerful point earlier: African countries now expect to be treated as partners…

Yes. African countries now want to be seen as partners with international actors and reject the colonialist approach of the West. A growing middle class of hundreds of millions of people is emerging in Africa, who expect peace, security, education, and work – at home, not abroad. If the political leadership fails to provide this, those in power are replaced, in many cases we see them democratically voted out of power.

Fears about migration are exaggerated: most African migrants move within a country or region, and when they go abroad, they choose their destination on the basis of historical links, so, of course, Europe remains an important destination, but the Global South, including China and Turkey, is also increasingly popular.

The well-qualified delegates of the African Union already represent a new vision, and their 2063 goal is for a continent that is developing along its own vision. Hungarian higher education can be a partner in this:

we will organise further trainings, staff weeks at the request of the AU and plan to send a Hungarian university delegation to Africa in 2026 in cooperation with the Hungarian Rectors' Conference.

The aim is to establish further concrete education-research collaborations with African institutions, including countries such as the old Kingdom of Swaziland, now officially known as Eswatini.

Written by Mercédesz Kovács-Csincsák

- Log in to post comments

University of Pécs | Chancellery | IT Directorate | Portal group - 2020.